TV and movie portrayals of real professions tend to be less than realistic, and the job of private investigator is no exception. But just because you won’t solve every case between 9 and 10 p.m. on Tuesdays doesn’t mean that becoming a private investigator isn’t for you.

TV and movie portrayals of real professions tend to be less than realistic, and the job of private investigator is no exception. But just because you won’t solve every case between 9 and 10 p.m. on Tuesdays doesn’t mean that becoming a private investigator isn’t for you.

What does it take to be a successful private investigator?

“You need to be intelligent, inquisitive and methodical,” says Dr. David Woods, a professor of criminal justice at South University’s Austin campus. Woods, who holds a doctorate in criminal justice and has worked as a police officer and a private investigator, also cites having an open mind, being proficient with technology and learning about people.

A good knowledge of the law is another necessity. Private investigators are regular citizens who must follow the law, but because of their profession they are held to a higher standard of legal knowledge than the public.

Most states require P.I.s to obtain a license, but the requirements vary widely based on where you live. Depending on the jurisdiction, even those with a law enforcement or military background may have to prove they have the necessary knowledge and skills.

Fulfilling the requirements may involve education, training courses, an apprenticeship or all three. In some situations, the education and training requirements can be met with a bachelor’s degree, such as the Bachelor of Science in Criminal Justice offered at several of South University’s campuses.

The work of a private investigator is not for everyone, but it can be an exciting way to earn a living for the right person. Like most careers, it has its plusses and minuses.

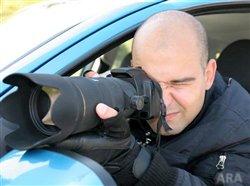

Working independently, as most P.I.s do, can mean a constant search for new clients. Other drawbacks include a lack of regular hours, dangerous situations and – much more often than danger – long periods of inactivity during surveillance work.

But Woods says that the fictional portrayals of private investigators are not completely untrue. The main resemblance to TV, he says, lies in the freedom and adventure of the job.

“It can take you anywhere, anytime,” he says. As for the disguises and subterfuge so often a part of TV shows, he says they may or may not be part of an investigation.

“A disguise is often part of surveillance work. But posing as someone you’re not is much rarer – maybe 10 percent of the job,” he says. “A good private investigator is never seen or heard until the investigation is complete.”

Other than the freedom it affords – which many may say is the best part – being a P.I. provides the ability to promote fairness and justice.

Because they see such a large number of cases, law enforcement agencies must limit the resources they can expend on each one. A private investigator, on the other hand, has the ability to focus his or her resources on one client at a time, which can yield better results.

“Many times, you are able to assist people who may have no other recourse available to them,” says Woods. “You can do something important and help someone out.”